|

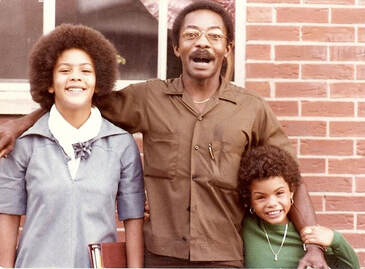

Kim, Charles and Kerry Kincy (Photo courtesy of Kerry Kincy) By Kerry Kincy Inspired by my father a Black entrepreneur, and by the Black Lives Matter movement in Connecticut and across the country, I set out to learn more about the experience of being a Black business owner and the importance of community support. What I discovered revealed a familiar and sometimes uncomfortable truth. My father was a Black inventor, a reader and a dreamer. Charles Kincy's best ideas came during the day, driving in a brown truck, in a brown uniform and delivering brown packages. He was an entrepreneur and created small Black-owned businesses in his community his entire life. For one of those businesses, Antiklectables, he purchased and sold Black art and Black memorabilia and it continues to operate today, nine years after his passing in June 2011. He was a successful businessman and a major contributor to the Black economy locally and beyond. A sense of agency—the intentionality for which he instilled the importance of supporting Black-owned business—was paramount to him. Ownership was always echoed in his conversations. “Owning” your history, your craft, your knowledge, your successes, and passing on your motivation to move forward in the direction of your Black ideas and dreams--those were his legacies. Charles was adamant, standing firm on the importance of reading, and was generous with reminders to pay attention to who had paid for those books to be written. It was important for him. He understood that racism was real and that it was often hidden beneath layers of narratives, disguised as nonfiction. Charles believed that despite being enveloped in racism, it was essential to know your own value and how your value contributed to the environment around you. I recently took to my neighborhood to explore other Black entrepreneurs in my community, to learn and discover more about the experience of being a Black business owner and the importance of community support. Bobby Perry, my neighbor, friend and pseudo-surrogate dad was my first source. Mr. Perry, now retired, and his wife, Olivia, have owned several businesses over the years. Mrs. Perry continues to provide custom tailoring services and Mr. Perry’s food truck was one of my favorites. We chatted in his garden, like we do most summer mornings while watering his collards. “Back in the day, I had so many people supporting me. Whenever there was something going on in town, the schools, the police events, anywhere, there was a need for good food, I would get a call. Larry McHugh, from the Chamber, was really good to me over the years and always made sure I was there. The biggest support came mostly from the white community,” he shared. I wondered why the majority of his support came from white folks more than folks that looked like us. He said, “There were a lot of good Black customers too, but sometimes people are threatened by someone else’s successes, and don't know how to act if they think you’re getting ahead faster.” That old saying about crabs in a bucket came to mind and sadly not particular to just Black folks. I later called to pose the question to Jessica, the Perrys’ daughter. Jessica grew up watching her parents work hard and create business opportunities that could provide for their family. “Growing up with parents as entrepreneurs, Perry’s Groceries, Perry’s Ice Cream, Excellent Designs by Olivia (a tailoring business) and Perry’s Hot food trucks, in addition to their full-time jobs, was simply a way of life and deeply rooted in us. Being your own boss while creating a good, quality product was and is our continued focus,” Jessica said with pride. Jessica and her daughters have followed in business, opening Queendom's Luxury Eyelash Extension line design in 2018, and later relocating to Central Florida. The business, which Jessica runs with her daughters, has grown exponentially over the last two years. She has also just recently started another business, Purpose Partners, which was launched in May and, despite the pandemic, has been well-received by the community. For business owner Jerome Mountcastle, the risk of entrepreneurship was like stepping into the unknown. Jerome was a troubled teen, and worked for a local car dealership detailing cars. He supplemented his income, “hustling drugs in the streets” to provide for himself and keep on top of child support payments that took most, if not all, of his paycheck most weeks. He decided to open his own detailing business, and although his first season was successful, when winter came and business dried up, he explained that he had to go back to the dealership. “I wasn’t aware of any business resources that could help me understand how to stay in business during slow seasons, and fell short in my financial responsibilities,” he said. But he kept at it, using the skills he acquired “hustli'n’”—quality goods, customer service, dependability, loyalty and word of mouth to build his business model.

It was clear to him those same strategies could be helpful in creating a solid business plan. “I found a way to create a life for my family doing what I love to do. I had come from nothing and now my children get to see and learn about working hard, about taking positive risks, about responsibility to self and about staying humble in all of it,” he said. Most of Jerome’s clients are between 50 and 70 years old and “mostly white people,” he laughed. I asked him why he thought his business had more support from whites in the community and he replied emphatically, “People are envious. They come work with you, see the money and think it’s easy. They quit and try and take your clients, never realizing that what I was doing was making a space for everyone to learn and feel successful. It was never just about me.” Jerome reminded me of my dad, who has worked full-time delivering packages for UPS and spent the rest of his time creating business ideas and making them real like the shoeshine stand he built and leased to other Black men in the community to exercise their entrepreneurial dreams. Charles also designed and created underwear for men and used the nonsensical stereotypes about Black men being more endowed to boost sales. He was brilliant at taking what he saw as oppressive and racist, rethinking it in a way that gave the power back to himself and other like-minded Black and brown dreamers. In part, I believe the paucity of witnessing and being exposed to successes in Black communities prevents Black folks from ever getting past the dream stage. We all have a dream, however the opportunities to see, learn, be exposed to and have access to Black successes are limited. The tools needed to continue to make those dreams a reality are learned and a muscle that must be exercised often. Environment is everything and access to programs and resources to help make real, entrepreneurial dreams come true are needed now more than ever in our Black communities. What I did discover is a common thread in my exploration of the experience of Black entrepreneurship. When asked who were their biggest supporters, the Black business people I talked to agreed that more whites than Blacks were to account for their repeat business. As a Black woman in business, I myself found the same to be true and only ever mentioned it in close company. But why? I wanted to dig deeper and understand some of the root causes and found these two interesting reads. Looking Beyond the Numbers: The Struggles of Black Businesses to Survive: A Qualitative Approach is a research study that aimed to use qualitative measures rather than quantitative to understand the barriers Blacks face in Black communities to be successful and sustainable.

I found a copy of a conversation that was published in Essence Magazine in 1984 between civil rights activists Audre Lorde and James Baldwin that gave me a different perspective and helped me to understand a little bit better. The conversation provides insight into the cultural structures where Blacks are already embattled in their own attempts within Black culture to escape being trapped into an Americans dream that systematically is set up to be unattainable. In an excerpt from “Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde” the two discuss race and business. The structures that naturally form in a culture where you're indentured in someone else’s idea of who you are, what you can be and offer the world are crumbling. The invisible biases that accompany Blacks in business are being exposed and remedying with a renewed sense of altruism. Allies are continuing to seek ways to support our Black entrepreneurs in creative ways. It’s driving positive changes across communities here and beyond. The substance of hope and faith have been evident in this new light of collective and cohesive strength the Black Lives Matter movement provides all of us. Today, I see the biggest shift in our young people. Recent events have provided a space for healing together and a place for young Black and brown people to come together in ways that force us to look at how we fight oppression and amplify our value together. “Seven million young people of color will have turned 18 since the last election,” wrote Dr. Melanye Price, a professor of political science at Prairie View A&M University in Texas, in her op-ed in the New York Times. “These newly eligible voters are primed for political participation after having consumed a steady diet of videos of racially motivated shootings and stories about the kidnapping of immigrant children. But their interest in politics is also thanks to the activism of groups like Black Lives Matter. There’s much more compelling evidence that we can motivate these young people to vote,” she wrote. Change is indeed coming and young people have created a shift in all of our perspectives on how to be more supportive for the greater good. As kids, my sister and I would rather clean and cut greens all day, than listen to our dad’s oratories about value, ownership and power. We would begrudgingly repeat back his words and subsequently remember it in our bones: “You are royalty. Your ancestors come from royalty and you must continue to honor and uphold these truths of who we are and carry on the legacy.” At the time, as fascinated as I was with the idea of coming from a royal family somewhere deep in the roots of our family tree, I found it hard to reconcile, since so many exchanges we shared as a family in our community and the world proved to be less than royal. My dad went to the extent of coming up with a code word for us to say when something or someone challenged our ideas of self, our value and our truth: “Kinciditia.” It was the signal that our truth would overpower any negativity that came at us; a sort of Kryptonite for our arsenal when dealing with racism in our everyday lives. As a kid, I never really understood why a sign that said “No Blacks, No dogs, No niggers,” would be important for his collection. I never understood his attraction to underground lithographs, prints and posters that depict Black folks as animals, in ugly blackface cartoons and always, always less-than. Today, I understand how deeply he felt about his Black experience, the experiences of Blacks in history, of how we as Black people were portrayed and how hard he worked his entire life to dismantle it. He worked equally hard his entire life to instill in us that we were valuable beyond any measure then what others set for us, and for me that has made all the difference. browse the shopblackct directory:

2 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed