|

By Elijah Manning As our nation continues to grapple with sins of the past, and finds ways to change our future for the better, there is one specific area that needs attention on a national level, but can start locally. I’m not talking policing, or equal housing, or so many other issues that have rightfully given us pause. To me, it starts with one important piece, and this is most important for children in the Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities. It starts with inclusive truth in education. When Black Lives Matter again took center stage, inequities, and inequalities that have been rampant in these communities were highlighted. The statement that has resonated the most, and became commonplace with many people was, “I never learned about that.” This statement came from many learned people, who began to realize they were missing very important pieces of their education. The missing pieces usually involved the learning about BIPOC, woman, and many other “minority” groups. Why are so many people missing something that should be taught regularly? Perhaps there is no singular, simplistic answer, but can be summed up in the words of spoken word poet, Regie Gibson, speaking on America’s relationship with its past. He said, “I think our problem as Americans is that we actually hate history, so we can’t really connect the dots. What we love is nostalgia. We love to remember things exactly the way they didn’t happen. History itself is often an indictment. And people? We hate to be indicted.” In communities around our country and even the world, we started to realize how much we missed. How much we relied on our friends in said “minority” groups to give the education completion that many never sought. For example, Christopher Columbus. We are taught the glorified version of who he was, but history leaves out the terrible things he did. That leaves us incomplete. It leaves us with half truths, and when we acquire new information from new sources, and new perspectives, we are left wondering why we were not given the full story. It breeds within us a discontentment that may never be reversed, due to our mistrust of the system that was set up to teach us, but hid the truth. This is the tip of the iceberg. We are awake to Juneteenth, and the story of what actually happened in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Anger over Aunt Jemima, the stereotype on the pancake and syrup label for years, no longer there. Some searched the history of minstrel shows and “Mammy” and learned about Nancy Green. If they had been taught who she was they would have realized why the label should have been changed years ago. Instead some fought about it and fought about Columbus statues, or Confederate general statues and flags, and many other things. This goes back to one crucial piece of information — we are not taught all the many perspectives of American history. "People have decided to say 'I don’t see color,' and while this may have the best intentions, it does more harm. If you don’t see my color then you don’t see all of me. You are missing parts of what make me unique and what makes me, me. You are missing an opportunity to learn from me and allow my life to help yours and denying me the opportunity in reverse." We have opportunities to grow as a nation by not limiting what we teach. We grow individually, but not always collectively. By not learning about all the accomplishments of the variety of people who have contributed positively to this country, we do a disservice to the work they did, and it limits our understandings of one another. If we expanded our curricula to be more inclusive and teach all “minority” achievements, it may help to cross our divides as people. And limit fear of each other. We are more than us vs. them. We are a collection of differences, our experiences. A collection of our ancestors, and our communities. As we all have differences, learning those differences allows us to realize what makes us different makes us great. People have decided to say “I don’t see color,” and while this may have the best intentions, it does more harm. If you don’t see my color then you don’t see all of me. You are missing parts of what make me unique and what makes me, me. You are missing an opportunity to learn from me and allow my life to help yours and denying me the opportunity in reverse. This is no different than missing parts of our history. If you aren’t taught the reason for the Civil War was majority slavery, or that George Washington had teeth in his mouth that used to be the teeth of slaves. Or you’ve never read “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, by Frederick Douglass, or haven’t learned the important work of Investigative Journalist Ida B. Wells. And learning about space and NASA is incomplete if Valerie Johnson isn’t discussed. We need to teach the advancements of minorities, as well as the setbacks faced. The importance of landmark Supreme Court Decisions, such as Brown v. Board of Education, Mendez v. Westminster, and the legislation that was passed as a result. Teach the Trail of Tears, teach about Japanese Internment Camps, The Fugitive Slave Act, The Tuskegee Experiment, and so many others. I could fill an overwhelming number of pages giving full accounts of all the African Americans, Latinx, women, Natives, and other minorities that have made significant contributions to the America we all know and love. Because we love it, it is our responsibility to do justice to the people who have come before and have made advancements, or positive changes. That have invented and solved, explored and written, ran from slavery, or ran for office, have challenged our thinking, and taught us new ways to think. Have fought for freedom, or helped save a life. I believe so much in this that I, along with others in the state, have founded a Facebook group that is dedicated to making these changes come about in our school systems. It is called the “CT Coalition for Educational Justice and a Culturally Responsive Curriculum.” We have members from all over the state as well as people from outside of our state looking to help us and themselves. We organize our information so it is readily available, we have resources dedicated to teaching, and training, and learning. We have a “Roll Call” where you can say what school system you are part of, and we have people willing to help consolidate resources to best share. We are looking to add more things community based, and communications based within the near future. If you would like to be a part, or learn more, find us on Facebook. It is up to us, all of us, too change things as they are currently, and make a better way forward for all. History, in particular, isn’t about teaching only positives. It is equally important to teach negatives. This gives us a complete picture. With that complete picture, we are granted the opportunity to make a decision how we feel about certain individuals, certain time periods, certain laws, certain cultures, and more. I will sum up with two important quotes from Frederick Douglass. The first is about slaves: “Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.” The second quote pertains to teaching children: “It is easier to build strong children, than to repair broken men.” If we teach our children a more inclusive education today, they will lead all of us to a better tomorrow. Click here to find Black-owned bookstores in Connecticut. BROWSE THE SHOPBLACKCT.COM DIRECTORY:

1 Comment

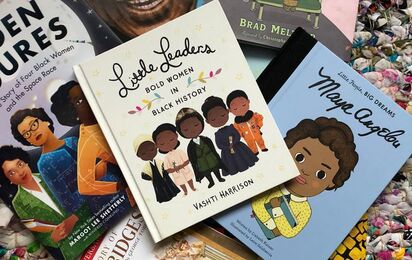

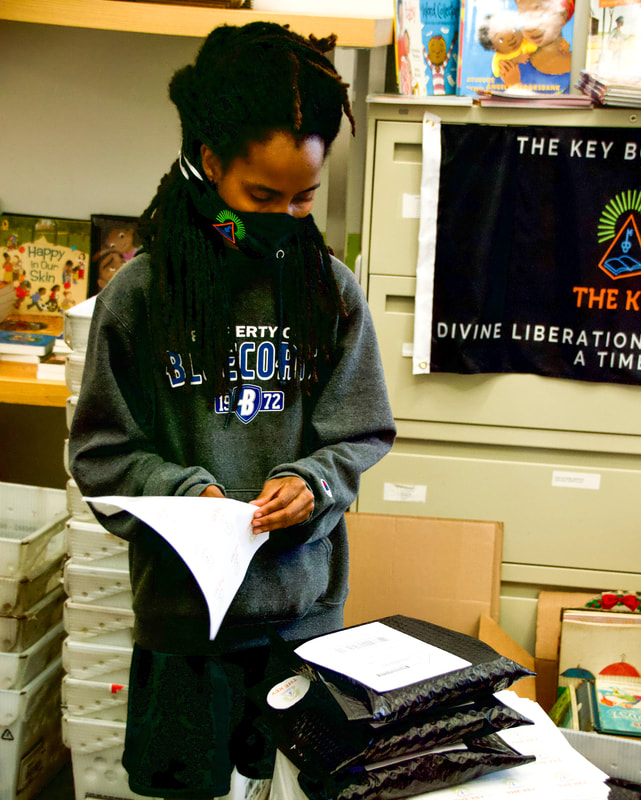

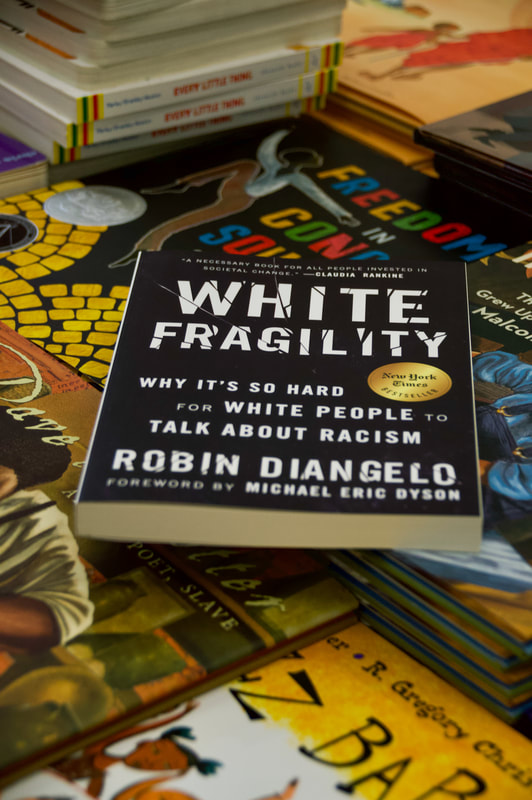

Photo courtesy of The Key By Jaclyn Wilson Inspired by the intimate interactions she had with booksellers as a conference attendee, Hartford, Connecticut resident and UCONN grad Khamani Harrison created The Key Bookstore in 2018. The Key is an Afrocentric mobile and online bookstore with carefully curated book lists focused on African American history, environmentalism, entrepreneurship, and spirituality. Harrison calls these subjects the four pillars of her business, using each as a guide when building a list of books. “Curation,” Harrison explains, “is everything.” Photo by Angel Thompson Photography Her booming business and thriving online community prove Harrison knows exactly what readers want. Harrison notes, “Some bookstores are missing the connection to the soul of a book reader.” Armed with that knowledge and dialed into the desires of readers like herself and her friends and neighbors, when she first began bookselling in 2018 Harrison would set up her mobile bookstore at community events, festivals, open mic nights, and pop up events, bringing knowledge right to the community, and providing books intended to enrich their lives. By building a dynamic, interactive space for online reader discussion, Harrison is filling the void left by traditional brick-and-mortar booksellers—a void that is filled when a reader is able to go online and interact with others who have also just read the same book and want to discuss the book’s content, pose questions, talk about their favorite parts, or get clarification. Like all businesses, Harrison’s has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting shut down, and is currently operating exclusively online at keybookstore.com. During the pandemic and since Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, Harrison’s business has “exploded.” Harrison explains, “People are looking for answers to take action with…the marches have led people to ask themselves ‘what do I need to know, how can I learn it, and where do I get it from?' The answer to that has been Black-owned bookstores like The Key.” Harrison also notes that part of the explosion of orders and subscriptions she’s seen is also due to The Key’s “White Ally Book List” that went viral on Twitter 10 days after George Floyd’s death, and was then picked up by Buzzfeed. Photo by Angel Thompson Photography “People are looking for answers to take action…the marches have led people to ask themselves ‘what do I need to know, how can I learn it, and where do I get it from?' The answer to that has been Black-owned bookstores like The Key.” Photo courtesy of The Key Harrison includes White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo on the “White Ally Book List” and notes that it is currently her best-selling title. A New York Times bestseller as well, White Fragility explores how the reactions of White people when confronted with issues of race can ultimately serve to maintain racial inequality. Other titles on the “White Ally Book List” include the most lauded and celebrated Black voices of our time, such as The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, Stamped by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi, Citizen by Claudia Rankine, and Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. They Key also offers other insightful book lists about the Black experience, such as Black365, which includes titles like Survival Strategies for Africans in America by Anthony Browder, The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B DuBois, while the Black History 101 book list recommends The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Narrative of the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, and The African Origin of Civilization by Cheikh Anta Diop, now in its 30th printing. No matter what readers may set out to learn, the book lists curated by The Key offer readers sophisticated recommendations and a dynamic online community with whom they can discover these books, and perhaps a new perspective on life. BROWSE THE SHOPBLACKCT DIRECTORY:

7/17/2020 1 Comment THE ECONOMICS OF RACISMPictured: Playa Bowls in West Hartford (Photo by Corey Lynn Tucker Photography) By Yvette Young People often ask, why does ShopBlackCT.com only focus on Black-owned businesses? The quick answer is because of the impact systemic racism has had on the Black community. Let’s use the “Monopoly analogy”—utilized by Kimberly Latrice Jones on social media—to highlight how systemic racism has impacted the economic reality of Black people in America. Imagine you are playing Monopoly for 450 years and for 400 of those years you are not allowed to have money, own any property or have any possessions. Then, for the next fifty years, everything that you earned was taken from you. You are playing for the benefit of the person you are playing against. You have to play to build their wealth and not your own. The question is, how do you win? The answer is that you can not win, because the game is fixed. Left: Reginald White, owner of The Crab Shack King - A Touch of Soul (Photo by Brenda De Los Santos Photography); Right: James Hanton, owner of The Singing Sliders (Photo by Corey Lynn Tucker Photography) "Wealth matters, and when you have played the 'economics of racism Monopoly' for centuries, you do not have the wealth required to start a business and sustain a business through hard times." Black people in America have been trying to catch up for centuries and when we put in the hard work and build our wealth it is burned to the ground like in Tulsa and Rosewood. This leaves us having to start all over again, forever trying to catch up. We are asked to catch up in a system that was established to allow us to remain poor. Practices such as not granting loans to Black individuals so they can buy property is a barrier. Justifying that Black people don’t qualify for loans because they have minimal wealth is a barrier. Using redlining practices to decide what funding goes into certain communities and if a loan to purchase property in those areas is justifiable is a barrier. Systemic racism limits access to financial resources that would allow Black people to invest in themselves and their businesses. Once a Black individual is able to acquire the resources needed to start a business, they are then confronted with the numerous barriers linked to maintaining that business. There is not an equal playing field for Black-owned businesses and they often do not have the resources to market and promote their businesses; often their revenue supports the cost of keeping the business open. Because of systemic racism, there are only a small percentage of Black-owned businesses compared to the total number of businesses in the United States. In fact, only 4.3% of the US’ 22.2 million business owners are Black (Brookings Institute Report, Feb 2020). Pictured: Your CBD Store Simsbury staff and co-owners, Katonya Hughey and Nakia Kearse. (Photo by Corey Lynn Tucker Photography) When faced with obstacles such as a pandemic, the impact on Black-owned businesses becomes insurmountable. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on Black-owned businesses. The Bureau of Economic Research reported that 41% of Black-owned businesses closed as a result of the pandemic, as opposed to 17% of white-owned businesses. Wealth matters, and when you have played the “economics of racism Monopoly” for centuries, you do not have the wealth required to start a business and sustain a business through hard times. This is why it is important to support Black-owned businesses, because without additional support, many will struggle to survive. ShopBlackCT.com was established to infuse support to Black-owned businesses by creating a platform for them to receive free marketing and promotion for their businesses, which in turn will help them reach new clientele, gain more customers and increase their revenue that will allow them to remain viable. Economic stability is crucial to the sustainability of these businesses. Annette Khodra from Nettie’s Gift Garden stated, “Being posted on ShopBlackCT.com has brought awareness to Black-owned businesses such as mine, which has increased consumer traffic to my site. It is a blessing to have my business being featured on this site. I am grateful for the opportunity to receive free marketing through my connection to ShopBlackCT.com. This site is truly an asset for my business.” Annette’s statement exemplifies why ShopBlackCT.com is critical and a much needed boost for Black-owned businesses. All small businesses matter, but when you look at the history of oppression the Black community has experienced and the lack of generational wealth as a result of that history, there should never be a debate about why there is a need to support Black-owned businesses. Pictured: A delicious meal from My Wife Didn't Cook (Photo by Gary Pope, GDA Weddings) browse the shopblackct directory:

Kim, Charles and Kerry Kincy (Photo courtesy of Kerry Kincy) By Kerry Kincy Inspired by my father a Black entrepreneur, and by the Black Lives Matter movement in Connecticut and across the country, I set out to learn more about the experience of being a Black business owner and the importance of community support. What I discovered revealed a familiar and sometimes uncomfortable truth. My father was a Black inventor, a reader and a dreamer. Charles Kincy's best ideas came during the day, driving in a brown truck, in a brown uniform and delivering brown packages. He was an entrepreneur and created small Black-owned businesses in his community his entire life. For one of those businesses, Antiklectables, he purchased and sold Black art and Black memorabilia and it continues to operate today, nine years after his passing in June 2011. He was a successful businessman and a major contributor to the Black economy locally and beyond. A sense of agency—the intentionality for which he instilled the importance of supporting Black-owned business—was paramount to him. Ownership was always echoed in his conversations. “Owning” your history, your craft, your knowledge, your successes, and passing on your motivation to move forward in the direction of your Black ideas and dreams--those were his legacies. Charles was adamant, standing firm on the importance of reading, and was generous with reminders to pay attention to who had paid for those books to be written. It was important for him. He understood that racism was real and that it was often hidden beneath layers of narratives, disguised as nonfiction. Charles believed that despite being enveloped in racism, it was essential to know your own value and how your value contributed to the environment around you. I recently took to my neighborhood to explore other Black entrepreneurs in my community, to learn and discover more about the experience of being a Black business owner and the importance of community support. Bobby Perry, my neighbor, friend and pseudo-surrogate dad was my first source. Mr. Perry, now retired, and his wife, Olivia, have owned several businesses over the years. Mrs. Perry continues to provide custom tailoring services and Mr. Perry’s food truck was one of my favorites. We chatted in his garden, like we do most summer mornings while watering his collards. “Back in the day, I had so many people supporting me. Whenever there was something going on in town, the schools, the police events, anywhere, there was a need for good food, I would get a call. Larry McHugh, from the Chamber, was really good to me over the years and always made sure I was there. The biggest support came mostly from the white community,” he shared. I wondered why the majority of his support came from white folks more than folks that looked like us. He said, “There were a lot of good Black customers too, but sometimes people are threatened by someone else’s successes, and don't know how to act if they think you’re getting ahead faster.” That old saying about crabs in a bucket came to mind and sadly not particular to just Black folks. I later called to pose the question to Jessica, the Perrys’ daughter. Jessica grew up watching her parents work hard and create business opportunities that could provide for their family. “Growing up with parents as entrepreneurs, Perry’s Groceries, Perry’s Ice Cream, Excellent Designs by Olivia (a tailoring business) and Perry’s Hot food trucks, in addition to their full-time jobs, was simply a way of life and deeply rooted in us. Being your own boss while creating a good, quality product was and is our continued focus,” Jessica said with pride. Jessica and her daughters have followed in business, opening Queendom's Luxury Eyelash Extension line design in 2018, and later relocating to Central Florida. The business, which Jessica runs with her daughters, has grown exponentially over the last two years. She has also just recently started another business, Purpose Partners, which was launched in May and, despite the pandemic, has been well-received by the community. For business owner Jerome Mountcastle, the risk of entrepreneurship was like stepping into the unknown. Jerome was a troubled teen, and worked for a local car dealership detailing cars. He supplemented his income, “hustling drugs in the streets” to provide for himself and keep on top of child support payments that took most, if not all, of his paycheck most weeks. He decided to open his own detailing business, and although his first season was successful, when winter came and business dried up, he explained that he had to go back to the dealership. “I wasn’t aware of any business resources that could help me understand how to stay in business during slow seasons, and fell short in my financial responsibilities,” he said. But he kept at it, using the skills he acquired “hustli'n’”—quality goods, customer service, dependability, loyalty and word of mouth to build his business model.

It was clear to him those same strategies could be helpful in creating a solid business plan. “I found a way to create a life for my family doing what I love to do. I had come from nothing and now my children get to see and learn about working hard, about taking positive risks, about responsibility to self and about staying humble in all of it,” he said. Most of Jerome’s clients are between 50 and 70 years old and “mostly white people,” he laughed. I asked him why he thought his business had more support from whites in the community and he replied emphatically, “People are envious. They come work with you, see the money and think it’s easy. They quit and try and take your clients, never realizing that what I was doing was making a space for everyone to learn and feel successful. It was never just about me.” Jerome reminded me of my dad, who has worked full-time delivering packages for UPS and spent the rest of his time creating business ideas and making them real like the shoeshine stand he built and leased to other Black men in the community to exercise their entrepreneurial dreams. Charles also designed and created underwear for men and used the nonsensical stereotypes about Black men being more endowed to boost sales. He was brilliant at taking what he saw as oppressive and racist, rethinking it in a way that gave the power back to himself and other like-minded Black and brown dreamers. In part, I believe the paucity of witnessing and being exposed to successes in Black communities prevents Black folks from ever getting past the dream stage. We all have a dream, however the opportunities to see, learn, be exposed to and have access to Black successes are limited. The tools needed to continue to make those dreams a reality are learned and a muscle that must be exercised often. Environment is everything and access to programs and resources to help make real, entrepreneurial dreams come true are needed now more than ever in our Black communities. What I did discover is a common thread in my exploration of the experience of Black entrepreneurship. When asked who were their biggest supporters, the Black business people I talked to agreed that more whites than Blacks were to account for their repeat business. As a Black woman in business, I myself found the same to be true and only ever mentioned it in close company. But why? I wanted to dig deeper and understand some of the root causes and found these two interesting reads. Looking Beyond the Numbers: The Struggles of Black Businesses to Survive: A Qualitative Approach is a research study that aimed to use qualitative measures rather than quantitative to understand the barriers Blacks face in Black communities to be successful and sustainable.

I found a copy of a conversation that was published in Essence Magazine in 1984 between civil rights activists Audre Lorde and James Baldwin that gave me a different perspective and helped me to understand a little bit better. The conversation provides insight into the cultural structures where Blacks are already embattled in their own attempts within Black culture to escape being trapped into an Americans dream that systematically is set up to be unattainable. In an excerpt from “Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde” the two discuss race and business. The structures that naturally form in a culture where you're indentured in someone else’s idea of who you are, what you can be and offer the world are crumbling. The invisible biases that accompany Blacks in business are being exposed and remedying with a renewed sense of altruism. Allies are continuing to seek ways to support our Black entrepreneurs in creative ways. It’s driving positive changes across communities here and beyond. The substance of hope and faith have been evident in this new light of collective and cohesive strength the Black Lives Matter movement provides all of us. Today, I see the biggest shift in our young people. Recent events have provided a space for healing together and a place for young Black and brown people to come together in ways that force us to look at how we fight oppression and amplify our value together. “Seven million young people of color will have turned 18 since the last election,” wrote Dr. Melanye Price, a professor of political science at Prairie View A&M University in Texas, in her op-ed in the New York Times. “These newly eligible voters are primed for political participation after having consumed a steady diet of videos of racially motivated shootings and stories about the kidnapping of immigrant children. But their interest in politics is also thanks to the activism of groups like Black Lives Matter. There’s much more compelling evidence that we can motivate these young people to vote,” she wrote. Change is indeed coming and young people have created a shift in all of our perspectives on how to be more supportive for the greater good. As kids, my sister and I would rather clean and cut greens all day, than listen to our dad’s oratories about value, ownership and power. We would begrudgingly repeat back his words and subsequently remember it in our bones: “You are royalty. Your ancestors come from royalty and you must continue to honor and uphold these truths of who we are and carry on the legacy.” At the time, as fascinated as I was with the idea of coming from a royal family somewhere deep in the roots of our family tree, I found it hard to reconcile, since so many exchanges we shared as a family in our community and the world proved to be less than royal. My dad went to the extent of coming up with a code word for us to say when something or someone challenged our ideas of self, our value and our truth: “Kinciditia.” It was the signal that our truth would overpower any negativity that came at us; a sort of Kryptonite for our arsenal when dealing with racism in our everyday lives. As a kid, I never really understood why a sign that said “No Blacks, No dogs, No niggers,” would be important for his collection. I never understood his attraction to underground lithographs, prints and posters that depict Black folks as animals, in ugly blackface cartoons and always, always less-than. Today, I understand how deeply he felt about his Black experience, the experiences of Blacks in history, of how we as Black people were portrayed and how hard he worked his entire life to dismantle it. He worked equally hard his entire life to instill in us that we were valuable beyond any measure then what others set for us, and for me that has made all the difference. browse the shopblackct directory:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed